News

Russia’s Early Plans for the Su-57: Over 100 Operational By 2022, New Variants and Exports to South Korea, Iran and India

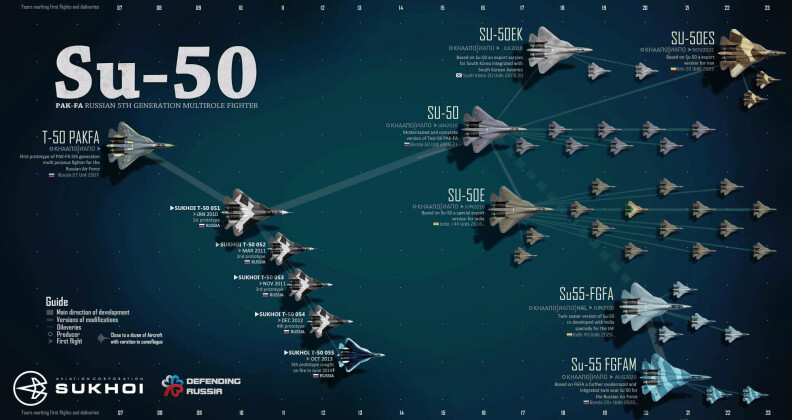

Russia’s Su-57 fifth generation fighter program has become a prominent symbol of delays and a struggle to move past Soviet era designs in the country’s defence sector, with the the first full squadron expected to be fielded only in 2024 while only six airframes have been delivered so far. While the Soviet Union began development of a fifth generation fighter over 40 years ago in the late 1970s, and was expected to have a technology demonstrator flying before 1995 and an operational fighter in 2000-2005, the state’s disintegration and near collapse of the Russian defence and broader tech sectors led to very significant delays in development. The result was the cancellation of the promising MiG 1.42 program and the privately funded and less advanced Su-47, and work on the new Su-57 which first flew in 2010 and was expected to enter service in 2015. Initial projections were for a fleet of 50 to be operational by 2020 and 200 by 2025, with the production numbers being significantly larger still as many airframes went to foreign clients. An infographic released by Sukhoi showed how the program was initially projected to evolve, with particularly notable insights into which countries were expected to be leading export clients and when new variants of the aircraft were expected to materialise.

It was initially projected that the Indian Air Force would be the first overseas client for the Su-57 as part of the FGFA program – a joint effort to develop a customised version with significant Indian technological inputs. These would begin delivery around 2017, with the last of the 144 units planned for Indian service joining the fleet around 2023. The second export client for the class was expected to be South Korea, which would acquire 20 fighters from 2018-2020 modified with Korean avionics. This came as the country had shown a significant interest in Russian fighters after the Soviet collapse, most notably the MiG-29 and Su-37 in the 1990s, which would complement its acquisitions of Russian tanks, air defence systems, ballistic missile technologies and other assets. U.S. pressure on Seoul was ultimately key to limiting defence ties from the 1990s, although the East Asian state would continue to acquire Russian technologies through transfer agreements which were less conspicuous than hardware acquisitions. The possibility of South Korean interest in the Su-57 in the late 2010s was not unthinkable at the beginning of the decade, particularly as U.S influence over the country appeared to wane and Korean trade with China came to far surpass that with the United States.

A third export client expected to procure 20 units of Su-57s from 2020 was Iran, which had shown an interest in high performance Russian interceptors in the past and fielded MiG-29 and Su-24M fourth generation jets purchased from the Soviet Union. The delayed date for Iranian purchases may have reflected concerns surrounding the UN arms embargo on the country, which expired only in 2020. Beyond these sales, Sukhoi also projected that a new fifth generation fighter derived from the Su-57 with a twin seat configuration would begin deliveries to the Indian Air Force in 2020, with 40 delivery between then and 2022, while the Russian Air Force would acquired 20 for its own use from 2021-2023. The derivative could mirror the development of the Su-30 based on the Su-27 airframe in the previous generation, potentially with an extended range and greater focus on command and control.

Delays to the Su-57 program mean the Russian Air Force is expected to acquire considerably fewer in the near term, and instead of transitioning to the class from the Cold War era Su-27 it has instead acquired over 128 Su-35s with more still on order. These represent significantly enhanced Su-27 derivatives with next generation engines, sensors, composite materials and avionics, which while overwhelmingly more capable are still far inferior to the Su-57 itself. Russia is still seeking to export the Su-57 today, although the nature of its client base has changed significantly. Initial hopes for sales to China were scuppered by the country’s rapid progress on its own fifth generation program the J-20, which is similarly a twin engine heavyweight design that has been produced in over 20 times the numbers of its Russian competitor and is in many respects more capable. India meanwhile pulled out of the FGFA agreement, although it is still considered a leading potential client potentially for license production or for off the shelf purchases with military leaders having expressed interest in both options. Iran also remains a possible client although it has more recently shown an interest in the Su-35 which could potentially be delivered much more quickly.

In South Korea’s case delays to the Su-57 program allowed the country to develop its own fifth generation fighter class the KF-21 which first flew in 2022 and is expected to enter service around 2027. Although far lighter and less ambitious than that Russia would have offered, the KF-21 program is expected to leave little room for further fifth generation fighter acquisitions despite growing ties between Seoul and Moscow in other fields. The possibility of Su-57 technologies being transferred to enhance the KF-21, however, remains significant and has several precedents in other Korean weapons programs.

Looking to other possible clients North Korea, although potentially highly interested and able to finance an acquisition, remains under a UN embargo which Russia is unlikely to risk violating as openly as a heavyweight fighter sale would require. Algeria on the other hand in the 2010s emerged as a leading client for Russian arms acquiring over 70 Su-30MKA fighters among other assets, with widespread reports and multiple indications from within the African state highlighting it could be one of the Su-57’s first clients. In Vietnam, too, local papers have repeatedly highlighted the high likelihood of an acquisition in the 2030s. Russian official sources have confirmed that a twin seat variant is under development mainly for export markets as initially envisaged, meaning the Su-57 could well prove successful and be widely deployed albeit a decade or more later than initially scheduled. This would still place Russia far ahead of its European rivals in moving past the fourth generation, but far behind China or the United States which deployed their first full strength fifth generation squadrons in 2017 and 2005 respectively. The Su-57 program highlights Russia’s struggle to pursue clean sheet fighter programs at anywhere near the rate the Soviet Union did, and the dangers of major delays both to the capabilities of one’s own air force and to one’s market share overseas. The program neverthless retains a number of strengths including its status as the only heavyweight fighter of its generation offered for export and the only one to have used standoff precision strike capabilities in combat – having been deployed against both state and non-state adversaries.