News

Will Russia Develop a Su-35 Twin Seater For Iran? AEW&C and Training Needs Make Second Officer Preferable

On January 15 the deputy head of the Iranian parliament’s National Security and Foreign Policy Committee, Shahriar Heydari, confirmed that the first Su-35 fighters would be delivered by the Iranian new year in March 2024. This follows a statement by the Commander of the Air Force of the Islamic Republic of Iran General Hamid Vahedi on September 4 that the service was considering acquisitions of Russian Su-35 fighter aircraft, and later reports from American sources in December that Iranian pilots had already begun training in Russia to operate the jets. Other than the indigenous Kowsar lightweight jets – a heavily enhanced derivative of the Vietnam War era F-5 which has been delivered in limited numbers – the Su-35 will represent the first fighter acquisition Iran has made since the early 1990s. Although the possibility of licence production of the Su-35 in Iran has been raised, it has been widely speculated that the first batch of two dozen aircraft have already been built – originally to meet Egyptian orders before these were cancelled by Cairo due to Western threats of economic sanctions. Should Iran move to adopt the Su-35 as its new primary fighter, which could potentially replace several of its seventeen currently operational units of Cold War era jets, the possibility could emerge of significant modifications to the aircraft for the country’s defence needs.

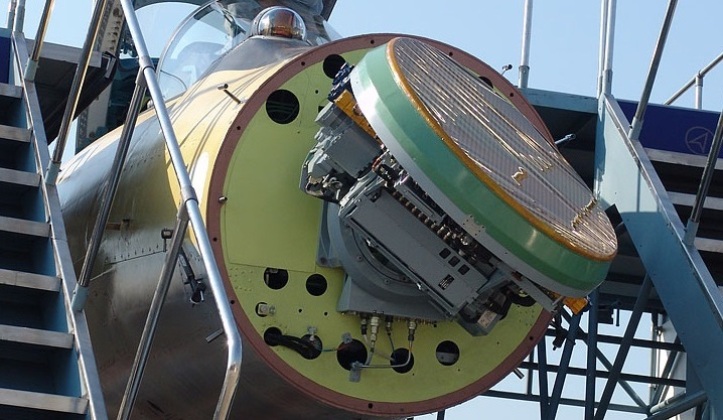

While the Su-35 was developed primarily as an air superiority fighter, much like its predecessor the Soviet Su-27 from which it is derived, the aircraft is also highly capable in strike, air defence suppression and anti shipping roles. In Iranian service, however, it is the fighter’s ability to guard the country’s airspace which is expected to be particularly prized, with other assets such as stealth drones and ballistic missiles already providing advanced anti surface capabilities. According to Iranian defence experts, air defence roles for the Su-35 will include not only deploying the aircraft to fire on intruders, but also leveraging its advanced sensors to serve as a force multiplier for existing Iranian Air Force and Air Defence Force assets through the provision of targeting data. The Su-35’s Irbis-E radar is among the largest in the world integrated onto a combat aircraft, and has a reported 90km tracking range against stealth targets and 400km against larger aircraft. It is supplemented by two L-band AESA radars in its wing roots which are optimised for tracking stealth aircraft. Although this triple radar suite, combined with advanced data links, could make the Su-35 an optimal airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft, particularly as Iran faces a growing threat from enemy stealth aircraft such as F-35 fighters and upcoming American B-21 bombers, the Russian jet’s single seat configuration is a notable shortcoming. Without a second seat, a single pilot will struggle to simultaneously fly a fighter and operate at the centre of an information sharing network.

A secondary AEW&C role was a primary reason why the Russian Su-30 series of fighters and MiG-31 interceptors were developed with twin seat configurations. The two were initially conceptualised as both interceptors and airborne command posts although the former evolved considerably to meet other roles shaped primarily by the needs of export clients. A single seat configuration also limits the Su-35’s options for pilot training, as while in Russia pilots typically train on the Su-30 – often the Su-30M2 variant – Iran lacks other aircraft with comparable 21st century avionics or a remotely comparable flight performance. Acquiring the twin seat Su-30 solely for a training role would impose a significant logistical and maintenance burden, however, due to the limited commonality between the Su-30 and Su-35, as while Russia operates both in large numbers fielding the two heavyweight classes in parallel would be impractical for the much smaller Iranian fleet. Should Iran proceed with large orders for the Su-35 beyond an initial batch of two dozen airframes, one significant possibility is that Russia could put a twin seat Su-35 variant into production to meet Iranian requirements.

Aside from the Su-57, for which a twin seat variant has reportedly already begun development for export purposes, the Su-35 is the only Russian fighter class that comes solely in single seat configuration. A single twin seat trainer airframe was notably built, the Su-35UB, although limited funding meant that it never moved beyond a prototype stage and the airframe differed very considerably from the final Su-35S production model. The large airframe of the Su-35 means a second seat could easily be accommodated with only a small sacrifice to fuel capacity and range, although it would still have by far the highest endurance combat jet in Iranian service. Whether a twin seater or other modifications of the Su-35 for Iranian requirements come to materialise remains to be seen, but the lack of other export orders due primarily to consistent Western threats against prospective clients means that Russia is likely to seek to maximise sales to Iran to keep production lines open, even if it is not likely to consider such modifications for its own Su-35 orders. The backbone Iranian Air Force formed by F-4D/E and F-14A fighters acquired in the 1970s notably all have twin engine configurations, with F-14s having frequently been used for AEW&C roles as a result, and although the Su-35’s far more modern avionics ease the burden on pilots considerably, Iran may well show a strong preference for twin seaters to the extent that they may outnumber single seaters in future orders.